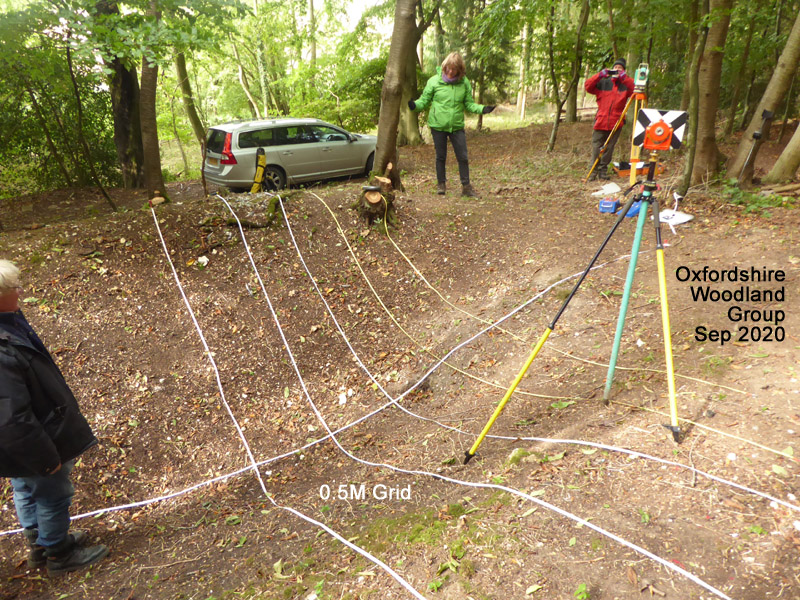

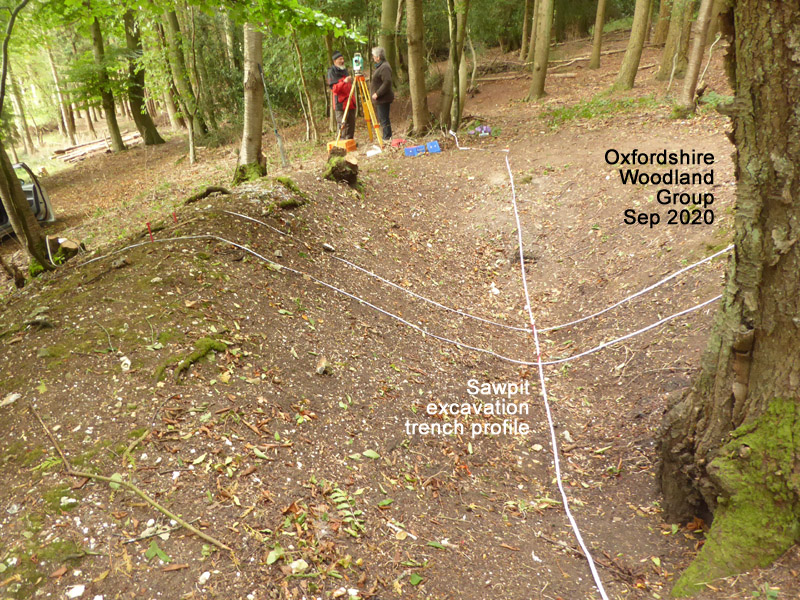

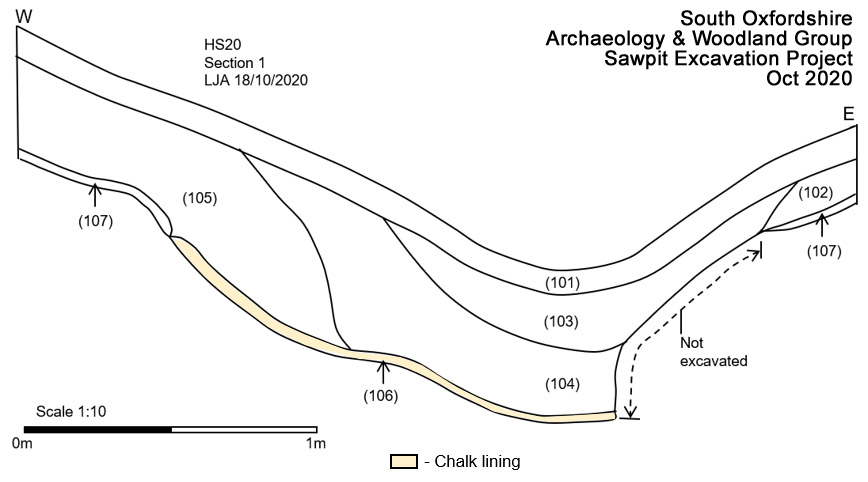

Many woodlands contain archaeological remains of former traditional woodland working methods such as sawpits. These pits were, whenever possible, located on sloping ground near to a woodland track.

The process employed is often referred to as pit sawing however in the case of Chiltern Hills sawpits this could possibly be misleading as most woodland pits are rarely more than 3-4 feet deep and hence could not accomodate an underdog as in a 17th century (brick lined) pit.

The photograph below is of Robert Spinner of Kent (Maskill, 2011) obtained by her from the various photographic collections stored at The Museum of English Rural Life, Reading, Berkshire, England.

It is more likely that hewn logs were simply upended into the shallow woodland pit by standing on one end of the log causing it to rotate and pivot on the upper bank then inserting a short legged trestle stool under the log to provide tempory support whilst a triangular saw brake was fitted.

The bottom of the log needs to be weighed down to prevent it from moving forward whilst the sawyer stands on top of the log. The historical evidence for the use of this approach to rip saw logs is illustrated in a Chinese postcard of sawing in Tsingtau circa 1900 where the bottom of the log is weighed down with a large rock.

This counter balance weight effect can also be achieved by employing an adjustable triangular sawing brake as demonstrated by Henry Russell at Frame 2010.

A long heavy log running across the length of the pit could then be attached to the apex of a brake using a Spanish windlas rope to raise the log just sufficiently to apply a downward force and moment on the brake apex to allow sawing to commence.

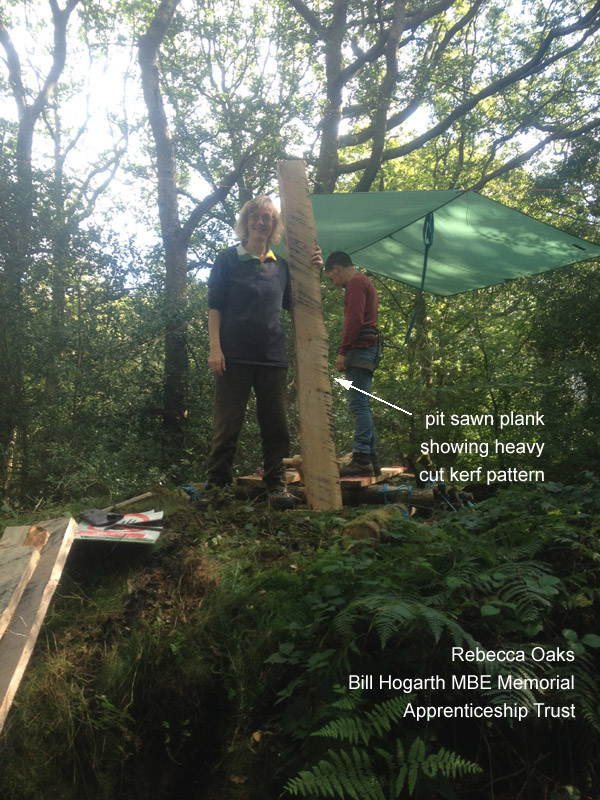

This process is called scie-sawing (as in the see-saw Margery Daw nursery rhyme). The log can only be sawn half way down its length using this process before needing to be be flipped over in the brake or turned in the pit to enable the log to be ripped down from the other end to meet the first saw cut (kerf). This gives rise to a very distictive conversion pattern that can be seen on early medieval buildings [Merchant's House, Tewksbury.]

This conversion method was also employed to convert cruck blades with the distinctive scie-sawn pattern able to be seen on the back face of an Oxfordshire Cruck blade.

The kerf angle is shallow towards the top end of the blade and steepens towards the centre indicating that the sawyer stood in a fairly fixed position adjusting the angle of cut as the saw came closer to his feet. This is clearly illustrated in a close up of Cruck Blade No 1 of the Oxfordshire Cruck shown above. This kerf pattern tends to suggest that the scie sawing process might well have been undertaken by one sawyer as the kerf advanced through the log and space underneath the log could no longer accomodate an underdog as is beginning to be illustrated in the Henry Russell photo above. A common assumption made by some historians is that rip sawing was done by men whereas women actually have a much better stomach muscle structure enabling them to undertake this process with relative ease as is ably demonstrated by Barabara Czoch on the Poland Synagogue reconstruction project.

Cruck blade No 2 illustrates the kerf overlap and hence also demonstrates the order in which the cruck blade was rip sawn (top down then bottom up) eventually resulting in the triangular snap area when the log came apart.

The other three faces of the cruck blade are hewn and a pronouced degree of grain tear out is evident most probably due to a dull hewing axe being employed. Waney edges are also evident demonstrating that a tree that was dimensionally just adequate for its chosen purpose was selected, felled and employed to good effect thereby minimising waste and limiting the required tree growing cycle (60 - 70 years).

Ken Hume

Executive Trustee - Oxfordshire Woodland Group

Ref:- MASKILL, L., 2011. The Farnham Park Sawpit, Farnham. Surrey : Rural Life Centre, un-numbered report.

|

Author

Author Sawpits

Sawpits